From First Presentation to Referral:

Stratified Decision-Making in Joint Pain Care

Patients typically present with pain in the knee, hip, shoulder or small hand joints, often accompanied by stiffness, reduced movement, crepitus, swelling or functional decline. Many cases reflect mechanical overload or early degenerative change,2 but metabolic health, low-grade inflammation and previous injury can also influence presentation. Recognising these patterns allows GPs and pharmacists to tailor management appropriately.

Although most joint pain is benign, clinicians should identify features requiring urgent investigation or referral, including:3

These presentations warrant timely imaging, laboratory testing or referral to rheumatology or orthopaedics.

Pharmacists should prompt urgent GP review when red flags are present, while GPs should arrange investigation and referral as needed.

Imaging should not be performed routinely.3 X-ray or MRI is most useful when:

Conversely, early osteoarthritis can often be diagnosed clinically without imaging. Imaging should be reserved for situations in which it changes management. Routine X-ray or MRI may reveal age-related changes unrelated to symptoms, which can increase anxiety without improving outcomes.

While imaging decisions sit with GPs, pharmacists play an important role in reinforcing when imaging is and isn’t appropriate.

Risk factors help determine management intensity and follow-up frequency.4 Key considerations include:

Patients with multiple risk factors may benefit from earlier intervention and closer monitoring due to higher progression risk. Pharmacists can identify risk factors during consultations and signpost patients to the GP when needed.

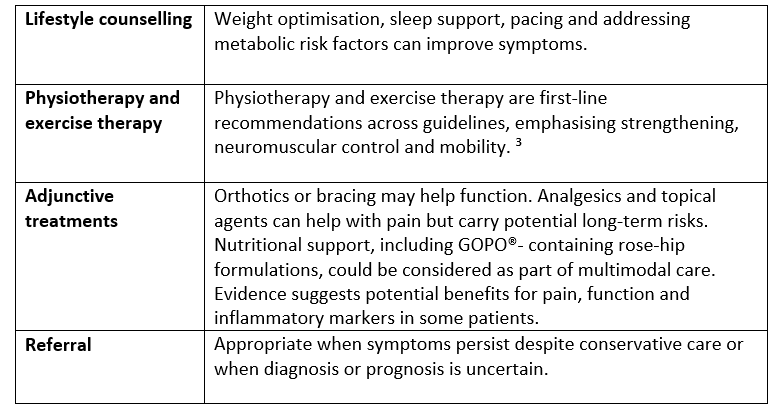

A stepwise pathway supports self-management and prevents unnecessary escalation:5

Most musculoskeletal (MSK) care guidelines emphasise early identification, education, exercise therapy, weight management and conservative treatment before imaging or surgical referral.6 A stepped model aligns with NICE, primary-care MSK pathways and multidisciplinary practice.

Useful tools include:

A carefully stratified approach supports timely diagnosis, effective early intervention, and more personalised care for patients living with joint pain.

1Aboulenain S, Saber AY. (2022) Primary Osteoarthritis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

2 Right Decisions (2024). Osteoarthritis - prevalence, risk factors, and non-radiographic diagnosis approach. NHS Scotland MSK-pathway.

3 NICE Guidelines (2022). Osteoarthritis in over-16s: Diagnosis and management. NG226 NICE guidelines.

4 Dong Y, Yan Y, Zhou J et al. (2023). Evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in middle-older aged: a systematic review and meta analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 29;18(1):634.

5 Arslan IG, van Berkel AC, Damen J et al. (2024). Patterns of knee osteoarthritis management in general practice: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. BMC Prim. Care 25, 2.

6 NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries (2024). Osteoarthritis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.